View an excerpt from the Interview with Ericka Huggins:

Reel Sisters Lecture Series & Stephens College MFA in TV and Screenwriting will present:

Our Stories. Our Medicine.

In Conversation with Ericka Huggins

Moderated by Valerie Woods

View an excerpt from the Interview with Ericka Huggins:

Reel Sisters Lecture Series & Stephens College MFA in TV and Screenwriting will present:

Our Stories. Our Medicine.

In Conversation with Ericka Huggins

Moderated by Valerie Woods

Join us at the next Chapter Meeting of Sisters in Crime with guest speaker Valerie C. Woods. The topic: Screenwriting Dialogue Tips Novelists Can Steal!

Recently, I had the pleasure of offering two writing workshops at the request of the Missouri Film Office in support of their Scriptwriting 101 initiative MOStories – The Missouri Stories Scriptwriting Fellowship. This is an international competition for screenplays and television pilot scripts with story lines set in the state of Missouri.

Recently, I had the pleasure of offering two writing workshops at the request of the Missouri Film Office in support of their Scriptwriting 101 initiative MOStories – The Missouri Stories Scriptwriting Fellowship. This is an international competition for screenplays and television pilot scripts with story lines set in the state of Missouri.

The morning session focused on film and the afternoon session was dedicated to television pilots. As an instructor for the Syd Field Screenwriting Method, I utilized the story and script structure based on Syd’s unique paradigm in both sessions, as it is applicable to writing for both film and television. In each medium your story will have a beginning, middle and end (though not necessarily in that order).

In a screenplay the original paradigm deconstructs a script with three-act structure. To start writing the script, the writer needs to know four things: The End, The Beginning, Plot Point I (that moves us into Act II) and Plot Point II (that moves us into Act III). Additionally, as Syd elaborated in his 2nd book, The Screenwriter’s Workbook, that three-act structure can be further defined with an additional Mid-Point (that links the first and second parts of Act II). This then creates four separate segments of a script, which fits with a basic television one-hour format.

Of course, modern television dramas can have five acts, or four acts with a tag either in the beginning and/or the conclusion. Syd further expanded the paradigm by including a “pinch” and/or an “inciting incident” which again helps in using it as a resource for writing one-hour dramas.

And, yes, a feature is longer than an episode of television. What about the page number references? How can I have Plot Point I near page 30 if my script is only 55 pages long? Hold on! Don’t be overwhelmed.

Always remember what Syd says about the paradigm: “We’re not talking numbers here, we’re talking form: beginning, middle, and end…It is not laid down in concrete. As a matter of fact, the great thing about structure is that it’s fluid; like a tree in the wind, it bends, but it doesn’t break.” I find this liberating and understand that page counts, where plot points appear, etc. are sign posts for me, the writer, in how a story develops – set up, confrontation and resolution – regardless of its length or medium. As Syd also says in The Screenwriter’s Workbook exercise on the first ten pages of a screenplay: “Screenplay form should never get in the way of your screenwriting.”

How did this play out in the MOStories workshop? The paradigm is important. Formatting is important. And, in Syd’s teaching, we are reminded not to get too rigid, just tell your story. What happens and who does it happen to? This is the focus of your writing. There were many questions in the workshop about proper format, act breaks, page count, and yes these are definitely things to keep in mind. And there are plenty of easy to access resources that give this basic information. In the workshop, though these were touched upon, primarily we explored how to get an idea from your head onto the page.

When an idea for a story comes to me it rarely, if ever, comes in a pure linear or narrative manner from beginning to end. Often the main character comes up who faces an unusual situation, like inadvertently witnessing a crime. Perhaps I want her to be the accidental detective who catches the perpetrator. Or perhaps she runs away and then has remorse and tries to fix it. There are flashes of scenes, dialogue, other characters, images, themes, etc. I write them down as they come, not trying to put them in a narrative line. Once all the flashes are on the page, it’s time to ask the big question? “So, what’s the story about?” This can be surprisingly difficult to articulate. It’s so exciting with all these great ideas and scenes, but really, what’s the story?

In The Screenwriter’s Workbook (Chapter 4) Syd recounted an experience he had with writer’s block. He was able to get through it once he recognized the importance of knowing your story clearly before you start writing the screenplay. Otherwise, you’ll get to a certain point and don’t know where to go from there. Syd came to understand during this particular experience of writer’s block that “The hardest thing about writing is knowing what to write.”

If your stories are born in the same way as mine, here is what I have learned to do. After reviewing all the exciting flashes of inspiration, it’s time to make choices, as guided by Syd’s paradigm: how do I want it to end? Where will it begin? What are the two places where the story shifts from Set-up to Confrontation (Plot Point I), and Confrontation to Resolution (Plot Point II)?

And here is what I really love about the paradigm, as Syd articulates in The Screenwriter’s Workbook: “The paradigm becomes your structural anchor.” Knowing the core of what I want to write, no matter how far afield I go with creative ideas, I never get lost or wander aimlessly in the middle of, say, Act Two. I can see the road ahead. And yes, sometimes the story takes a wild tangent and maybe it won’t end the way I planned. That’s not a failure. It’s a revelation. (And it’s happened more than once!) And I know the revelation would not have come without first following the structure. And so, what I hope I was able to communicate to the writers in that workshop (and in this recap) is to remember this: The form of the paradigm is not a set of unwavering rules, rather it is a resource that functions as a map of your core story that allows your screenwriting to fluidly traverse the full range of your imagination.

Originally posted on Syd Field – The Art of Visual Storytelling

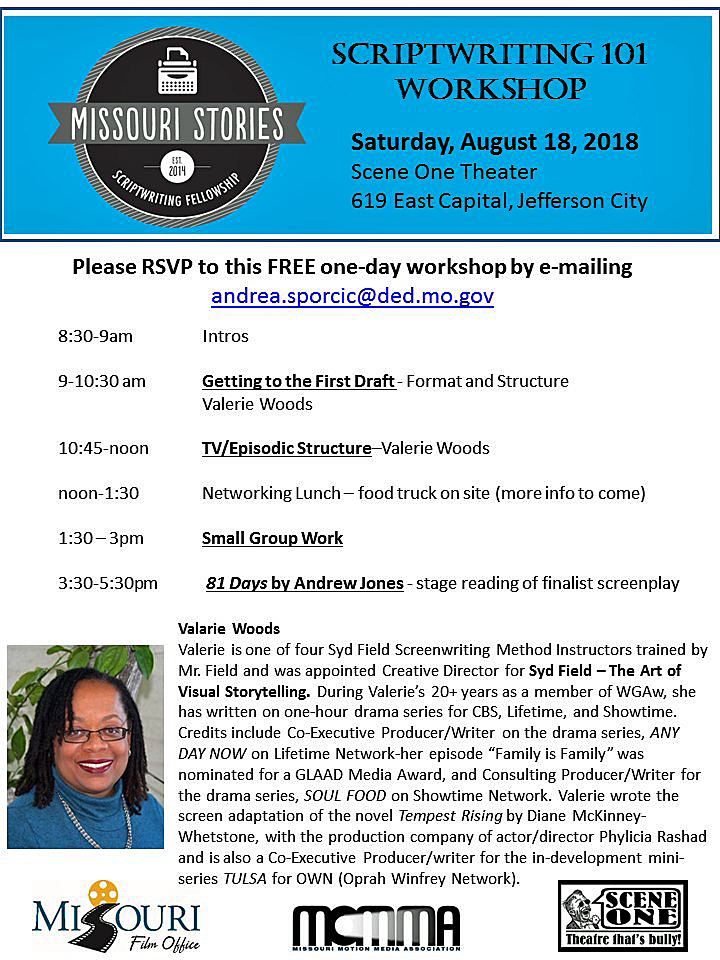

Had a great day offering the Scriptwriting 101 Workshop sponsored by the Missouri Film Office.

(l-r): Stephane Scupham, KC Film Office, Valerie Woods, Syd Field – The Art of Visual Storytelling, Facilitator, Andrea Sporcic, Missouri Film Office, Andrew Jones, MOStories Finalist, Screenwriter/Director

Wonderful group of creative Missouri writers who engaged fully in the Story Structure presentation based on the Syd Field Screenwriting Method and Paradigm, as well as the TV/Episodic Structure workshop. It was a pleasure facilitating both workshops!

Valerie C. Woods – Author, Publisher/Editor, Writing Coach, Writer Producer

For many writers, the start of a new year is the time to set deadlines for the next twelve months. You may have hit all the deadlines you charted the previous January, or maybe not. The dawn of a new year has such potential. There’s nothing to be done about the year gone by. Let it go. You either made your deadlines, or you didn’t.

As this year draws to a close, I made most of my deadlines. But before moving on to the coming year so full of possibilities, I decided to take a look back. How did I miss some of the deadlines I set for myself?

In Syd Field’s book The Screenwriter’s Problem Solver, I read something that helped me reconcile the progress of my writing, or intermittent lack thereof: “Writer’s Block. It happens all the time. To everybody. The difference is how you deal with it. How you see it.”

How did I deal with it? I did other things. I teach. I go to two different writer’s groups. I met friends for coffee. Read other people’s scripts. You know, things other than figuring out why I wasn’t finishing what I started. I basically, as Syd calls it, “hit the wall.”

Syd goes on to say: “If you can look at it [writer’s block] as an opportunity, you will find a way to strengthen and broaden your ability to create character and story. It shows you that maybe you need to go deeper into your story, and strive for another level of richness, full of texture and dimension.”

This brought me to a few critical questions. First of all, why tell this story? Why tell it now, at this point in time? Sometimes I find that I’m writing a story to make sense of a personal experience. Other times, it’s just an intriguing idea sprung from my subconscious or the zeitgeist or a response to something I’ve witnessed or read, and felt strongly that it needed to be dramatized. As Dr. Maya Angelou said: “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.”

What was my untold story? Did I even have something to say? Of course, the inner critic has a few things to say about this. Things like, ‘What even made you think this was a good idea?’ Or something along the lines of ‘Why didn’t you take that Write-a-Screenplay-in-30-days” challenge? Actually, when I’ve tried those 30-day challenges, I can do them. It’s just those 30 days aren’t consecutive; I’d write five straight days one month, but only two the next, and none for six weeks, while other life situations took over, and on and on. I would be distracted and at loose ends. I’d need to pause and ask, ‘What was it I was trying to accomplish, again? ‘

This brought me to another quote of Syd’s, this one near the conclusion of his book Going to the Movies. Syd is speaking about why he teaches: “I wanted filmmakers to make great movies that would inspire audiences to find their common humanity.”

This statement hit a chord with me. “…inspire audiences to find their common humanity.” Wasn’t this why I became a storyteller? To make a connection? To understand the commonalities of the human experience no matter who we are?

Scientists and anthropologists tell us that we are a species of storytellers, even before the written word, as seen in prehistoric cave drawings. Apparently, we humans have always told stories to makes sense of the chaos and share whatever insights we’ve gleaned to connect with others. Stories are not merely entertainment – they are learning experiences, culture creators, expressions of the heart and compassion – stories tell us who we are. Or at least, who we hope to be.

We’ve evolved from drawings on cave walls, but that’s just an evolution of storytelling technology – from cave to screen.

Syd teaches: “Movies are all about story. No matter who we are, or where we live, or what generation we may belong to, the singular aspects of storytelling remain the same.

This is echoed by George Lucas, creator of Star Wars and Indiana Jones, and founder of Lucasfilm and Industrial Light & Magic, when he states: “A special effect without a story is a pretty boring thing.”

I followed Syd’s advice to look at writer’s block as an opportunity to go deeper into my story. Soon, it became clear that the block arose because I had become so caught up in the process of putting the words on paper, that I’d lost sight of why I was telling the story. I had to come back to the core purpose of writing a screenplay – to tell a good story.

The time it took to become re-acquainted with my initial inspiration was a release. The opportunity to step deeper into my character’s dramatic need allowed me to be firmly established in the origin of their journey and ultimate goal. Now, there is no wall to hit, only creative opportunities to explore. Perfect timing as I set deadlines for the coming year!

As we move into the New Year, may your writing flow with ease… and if you hit a wall, remember these words from Syd Field to carry you through:

“If you understand that being dazed, lost, and confused is only a symptom, this “problem” becomes an opportunity to test yourself. Isn’t that what life’s all about – putting yourself on the line in a situation where you test yourself to rise to another level? It’s simply an evolutionary step along the path of the screenwriting process.”

–The Screenwriter’s Problem Solver

Happy New Year!

Originally posted on sydfield.com

Front Row, l-r: Dan Milano – (Robot Chicken, Greg the Bunny), Valerie C. Woods – (Any Day Now, Soul Food)

Middle Row, l-r: Salam Al-Marayati – MPAC, President, Sohrab Noshirvani – (Dry River Road, Junkyard Dogs),Y. Shireen Razack – (Shadowhunters: The Mortal Instruments, Haven), Sue Obeidi – MPAC Hollywood Bureau, Director

Back Row, l-r: Cherien Dabis – (Empire, Quantico), Chris Keyser – (Party of Five, The Last Tycoon, Tyrant)

The The Writers Guild Foundation and the Hollywood Bureau of the Muslim Public Affairs Council (MPAC) present a discussion on creating more authentic representations of Islam and Muslims in film and television. The panel will be moderated by Valerie C. Woods.

See the article from The Hollywood Reporter – Industry Panel Suggests Ways to Better Represent Muslims in Film and TV.

Panelists (l-r): Monica Macer (Queen Sugar, OWN), Shernold Edwards (Hand of God, Amazon), Dawn Kamoche (Sharp Objects, HBO), Dee Harris-Lawrence (Star, FOX), Valerie Woods (Soul Food, Showtime)

The Writers Guild Foundation event, co-sponsored by Stephens College MFA in Television and Screenwriting on January 13, 2017, was a great success. The panel, moderated by writer and BooksEndependent publisher, Valerie C. Woods, engaged the participants with their wisdom, humor and real-world advice on the evening’s topic – “Writing Outside the Color Lines: Women Writers of Color or Storytelling and Perspective”. A lively Q&A following the discussion extended the evening past its scheduled ending time.

Thanks to Chris Kartje and Enid Portuguez at the WGF, and Ken LaZebnik and Khanisha Foster of Stephens College for a wonderful evening!

There it is. The blank page. Or screen. It’s perfect, pristine, shimmering with possibilities. You want the words you impart on this perfect canvas to be worthy. To flow with lyrical, righteous, and passionate… stuff. No, scratch that, not ‘stuff’ – it must be classic Oscar, Emmy, Tony award winning scriptness. Wait. What? ‘Scriptness?’ Ok, perfect prose, poignantly profound… stop! Scratch that, too. And now it’s ruined. The blank page, which was once so full of hope, is now ruined. Crumple paper, or delete, delete, delete. Time for coffee.

Such pressure, the blank page. Why is it so hard to allow for imperfection? It’s not called a rough draft because it’s perfect. So go ahead and be a RoughWriter!

In his book,”Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting” Syd Field put it very bluntly, “Let yourself write sh*tty pages, with stilted, direct, dumb, and obvious dialogue. Don’t worry about it. Just keep writing. Dialogue can always be cleaned up during the rewrite. ‘Writing is rewriting’ is the ancient adage.”

This advice applies to ALL writers, not just screenwriters. It is the only way to get through a novel, a play, short story, or novella. I know, because I’ve written at least one of each in that prior list, and Syd Field’s advice got me through each project.

Currently, I am a Mentor for a group of very talented MFA screenwriters. In the first semester, each student selected the topic of their screenplays, wrote beat sheets, and narrative outlines. At this point, two writers decided they no longer wanted to write the stories they’d chosen, and switched – went through the earlier process again and then began writing script pages. Then a third writer decided her pages were awful, her story was stupid and it was boring. One of the first two writers, worried that well, maybe the new idea wasn’t good either.

To clarify, none of the stories were boring. What I was hearing from these students was doubt, resistance… you know, fear of failure. They had each done great work. But the Inner Critic had moved to the foreground and was doing its best to get them to give up.

What to do? It was time for the talk, as follows:

First drafts are never perfect. This is where inspiration meets the craft of writing – putting in the work, no matter if it sucks at first. Do not listen to the Inner Critic in the rough draft, or you’ll never get to the final draft.

As you begin, often the I.C. will tell you it’s boring, it’s not working, change the opening, drop this project, what the hell were you thinking, you have nothing to say…

Do. Not. Listen.

You were excited about your story for a reason. Self-doubt, masquerading as the Inner Critic, disguises itself with making you feel bored, or that you don’t like it anymore. This is where the work of your Outline is absolutely vital.

Just follow the Outline. Even if you think it’s terrible.

It’s amazing how objective we can be once the rough draft – the ugly draft – is completed. You can then see where to improve, edit, bolster, etc. When you start writing, your creative mind is still muddling through and the worst thing to do is to stop. So keep going.

And yes, you’ll make some adjustments as you write – but keep writing and don’t throw out or disparage your Outline. It is your road map. Let it guide you.

Please do not let your Inner Critic slow you down!!!

So, the good news is, each student responded with flying colors. They wrote through the doubt and came through on the other side. Writing through the pain of not-quite-inspired work solved story problems. By completing what might be a lousy scene, it became clear what wasn’t working, because it was no longer a vague jumble in the brain. It was right there in all its ugly glory, ready for the writer to apply the craft of revising and polishing. It’s truly a relief. And some of what was thought to be bad looked pretty good!

Staying true to what inspired you in the beginning, even when it didn’t feel like it was working, is how wonderful screenplays get written, and how they get made.

In “Selling a Screenplay: The Screenwriter’s Guide to Hollywood” Syd wrote: “What intrigues anyone in Hollywood, what propels someone into an active mode …is something that strikes them emotionally.”

And that starts with the screenwriter, television writer, playwright or author. Stick with what struck you emotionally when the storytelling process began. It will shine through in the end.

As this year draws to a close, and we are poised for new adventures in storytelling as a new year begins, remember: When the writing gets rough, the RoughWriter keeps going.

Happy writing!

posted by Valerie C. Woods

on December, 29

The post The RoughWriter appeared first on Valerie C. Woods.

In a previous post, I wrote about what indie authors could learn from indie filmmakers. As my writing often alternates between writing novels and screenplays, there are also screenwriting tools that can assist novelists.

One of the most valuable “oh, I get it!” moments studying with screenwriting mentor, Syd Field (1935-2013), was the first time Syd spoke about his groundbreaking Paradigm. More specifically – Syd stated that the first thing needed to begin was to know the end. As a young writer, this was a bit of a surprise.

At the time, my writing process was something like “wow, this is a good idea! The character would be this, they would do this and there would be a love interest, and they work at something amazing, etc. etc.” Dialogue and scenes would sprout and I’d write them down and generally let the story tell me what it was. Which is not such a terrible thing… at first. Getting the first flush of inspiration out and onto the page as quickly as possible is important, because I am so easily distracted.

However, there always came the time when I’d have to stop and ask, “so where does it all end?” Where am I going with this story? What is the resolution? And that’s when I go back to the Syd Field Paradigm and the four things the writer needs to know to begin writing:

The End

The Beginning

Plot Point I

Plot Point II

As Syd also explained in the seminar I first attended, writing a screenplay is a lot like planning a vacation. Rarely does anyone just show up at the airport and take whatever flight is next. If they do, I bet there’s a really good story in there somewhere! However, in order to know what to pack, how much money you’ll need, where you’ll sleep, etc. you need to know your destination. You’ll want to pack sandals, perhaps when going to India rather than, say ski boots.

The Paradigm is a road map to get you started. And, like any great adventure, there’s no telling if everything will go according to plan. It’s like that old proverb: “If you want to make God laugh, go ahead and make plans.” Just as unexpected excursions and detours make for really good road trips, the writer is free to go on an interesting tangent and not lose sight of the main plot because the Paradigm is a fluid guide that allows for inspiration and imagination, with landmarks to get you back on track.

For instance, just because you said Plot Point One was when the character woke up from a coma, doesn’t mean it has to stay that way. As you write toward the plot point, you might find that maybe the character stays in the coma and someone who was supposed to be a minor character has to step up and fulfill a great destiny. But I believe you wouldn’t have come to that point had there been no destination in which you were heading.

For me, having a story point to write toward gets the process going, even if it turns out I don’t end up there.

Using the Paradigm has saved me from writer’s block and out-of-control subplots. And, the bonus to this screenwriting Paradigm is that it has also worked when I write novels and television shows.

It’s ok to write down inspiration even if you don’t have a clear vision of where it’s going. But once the flash of inspiration has expended its fire, it’s time to invoke the craft of writing. It is the craft of story structure that provides the foundation through which inspiration is woven.

In Syd’s book The Screenwriter’s Workbook he states: “You must know what the resolution of your story line is. I don’t necessarily mean the specific scene or sequence at the end of the screenplay but what happens to resolve the dramatic conflict. If you don’t know the ending of your story, who does?”

You are the guide on this journey and in order to reach the destination, the first thing to know as you anchor those flashes of inspiration and begin the trek home is… where does it all end?

posted by Valerie C. Woods

on January, 15

A strong woman, Mrs. Mary E. Jones Parrish, wrote the book on the following event. This is my summary of those events.

Once upon a time, a group of black protesters who were against mob rule, set out to support their local sheriff in protecting a young prisoner from being lynched. It was a time when open carry of firearms was legal. Many of the black protesters were veterans of The Great War. They were proud citizens who felt it was their right to step forward and maintain the peace and the rule of law.

They were rightfully concerned, because just nine months earlier, a white mob had taken a white prisoner from custody and lynched him. The crowd of white citizens was so large the police directed traffic to allow the extra-legal execution to take place without interference. However, once mob “justice” had been served, the crowd surged forward to rip souvenirs from the corpse.

This was the mentality facing the protesters of this time and place – 1921, Tulsa, Oklahoma. If the authorities chose not to protect one of its white citizens from a lynch mob, what hope was there for a black citizen without support from his community?

However, the white mob surrounding the courthouse was incensed that these black citizens would question their actions. Who were they to stand and voice an opinion? By noon the following day, this white mob organized and executed the largest riot against a black community in the history of our nation. With guns, fire and bombs, the once prosperous community known as Greenwood, the Black Wall Street, was pillaged and burned until it resembled a bombed-out village from the recent war in Europe.

Those black citizens who survived, including Mrs. Jones Parrish and her daughter, were rounded up and placed into detention camps. Martial law was declared. These black citizens could only be released through the authority of a white citizen. Men, women, children.

No one from that white mob ever served time for these crimes. In fact, the official grand jury blamed the destruction on the black protesters for daring to come forward, stating that propaganda had been: “accumulative in the minds of the negro which led them as a people to believe in equal rights, social equality and their ability to demand the same” – Tulsa World, June 26, 1921, p. 8. A message had been sent and the grand jury condoned it.

I was drawn to tell this story now in light of current events.

When a (white) front runner in the 2016 presidential campaign says to his supporters, in response to (primarily black) protesters, “I love the old days. You know what they used to do to guys like that when they were in a place like this? They’d be carried out in a stretcher, folks.” we need to talk about the “old days” to which he refers. Further, this same front runner now predicts that if he does not get the GOP nomination, there will be riots.

There is a well-known cautionary statement: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” (Charles Santayana, The Life of Reason, 1905).

Here we are in the 21st century, and it seems there is an existing segment of our country who do remember the past and are really eager to repeat it.

This year, Memorial Day weekend 2016, marks the 95th anniversary of “the old days.” A survivor and strong woman of that period, Mrs. Mary E. Jones Parrish, wrote the first book to detail the tragedy, based on her experience and the testimony of other survivors.

#WorldStory16 http://tulsahistory.org/learn/online-…

#WorldStory16 http://tulsahistory.org/learn/online-…

posted by Valerie C. Woods

on March, 20